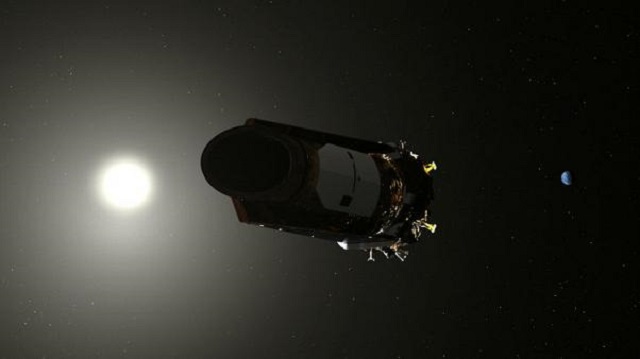

NASA retires its planet-hunting Kepler space telescope

NASA has decided to retire its Kepler space telescope that had run out of fuel needed for further science operations.

Working in deep space for nine years, Kepler has discovered more than 2,600 planets from outside our solar system, many of which could be promising places for life, Xinhua news agency reported on Tuesday.

The spacecraft will be retired within its current, safe orbit, away from Earth, according to NASA, the report said.

“As NASA’s first planet-hunting mission, Kepler has wildly exceeded all our expectations and paved the way for our exploration and search for life in the solar system and beyond,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

“Not only did it show us how many planets could be out there, it sparked an entirely new and robust field of research that has taken the science community by storm. Its discoveries have shed a new light on our place in the universe, and illuminated the tantalising mysteries and possibilities among the stars,” said Zurbuchen.

A recent analysis of Kepler’s discoveries suggested that 20 to 50 per cent of the stars visible in the night sky were likely to have small, possibly rocky, planets similar in size to Earth, and located within the habitable zone of their parent stars, which means they’re located at distances from their parent stars where liquid water, a vital ingredient to life as we know it, might pool on the planet surface.

“When we started conceiving this mission 35 years ago, we didn’t know of a single planet outside our solar system,” said the Kepler mission’s founding principal investigator, William Borucki, now retired from NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley.

“Now that we know planets are everywhere, Kepler has set us on a new course that’s full of promise for future generations to explore our galaxy,” said Borucki.

Launched on March 6 in 2009, the Kepler space telescope combined cutting-edge techniques in measuring stellar brightness with the largest digital camera outfitted for outer space observations at that time.

Originally positioned to stare continuously at 150,000 stars in one star-studded patch of the sky in the constellation Cygnus, Kepler took the first survey of planets in our galaxy and became NASA’s first mission to detect Earth-size planets in the habitable zones of their stars.

Four years into the mission, after the primary mission objectives had been met, some mechanical failures temporarily halted observations. But the mission team managed to devise a fix, switching the spacecraft’s field of view roughly every three months.

This enabled an extended mission for the spacecraft, dubbed K2, which lasted as long as the first mission and bumped Kepler’s count of surveyed stars up to more than 500,000.

“We know the spacecraft’s retirement isn’t the end of Kepler’s discoveries,” said Jessie Dotson, Kepler’s project scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley.

Kepler’s more advanced successor is the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), launched in April.

TESS builds on Kepler’s foundation with fresh batches of data in its search of planets orbiting some 200,000 of the brightest and nearest stars to the Earth.